The Size Of A Tiny Crater On The Moon

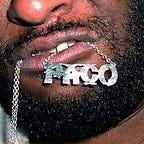

Reflections on the deep impact of New York graffiti artist & party flyer designer Phase 2

12 min readJan 20, 2020

Phase 2 was a hard man to find. It’s why Jerome Harris, a graphic designer and design director at Housing Works in New York, reached out to me––a culture writer, designer, and unabashed fan of Phase 2––and others, like film director Charlie Ahern (Wild…